Story and Interviews by B.N. Duncan

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]t is a much-neglected fact that some people in Berkeley who exist on the down-under margins of society — including some homeless people — do valuable work in artistic media. Five outstanding examples are Richard List, Mike “Moby” Theobald, Gino Alvarez, Julia Vinograd and Ace Backwords.

I interviewed these five artists recently, asking them two related questions posed to me by Street Spirit editor Terry Messman: “Why is valid, vital art arising from the fringe?” and “Why have the deprivations and injustices of poverty and homelessness led some Berkeley artists to creative expression?”

These five artists are more original and authentic than many people living in the mainstream. Berkeley has a significant proportion of socially marginal people, including homeless people, who comprise some of the spiritual, mental and creative wealth of the city. In Berkeley, the term “street people” has often pertained to people of vital spirit and inspiration, although increased abuses in our mechanical, bureaucratic, money-and-power system of established institutions tend to obscure this meaning.

The establishment gets more corrupt and phony, and seeks to cast out or destroy more of the people who have a strong and true self. Many people of original or luminary bent have been drawn to the exceptional town of Berkeley, even some people who know they will have to live on the street. (“Man does not live by bread alone.”) Berkeley would benefit by being aware of the treasury of people on its fringe who create art, live valuable lessons of life, set instructive personal examples and have messages and visions to give. Working on this article reminds me that art is very much about humanity.

Richard List: How Pain is Transformed into Art

Richard List, who lacks a building to live in, has a storm inside of emotional pain and violent urges, while possessing humor, sensibility and strong positive interests in learning and accomplishment. He is rebellious while practicing good will. He has the courage for adventure, but is also an alarmist. In his “Plop Art,” List uses improvised objects, colors, images and the printed word to create public exhibits and street-theater demonstrations without the sanction of officials. He communicates warning signals and messages of guidance in a troubled society, and expresses a sense of outrage and crisis, while providing non-threatening entertainment for people.

B.N. Duncan: Why do people on the fringe of society create vital art?

Richard List: There’s a tremendous amount of experiences where people have suffered a lot, and if you can just get them to draw it, it doesn’t matter how crudely, it can have incredible power and meaning.

I myself have experienced a lot of pain that I need to express one way or another. Art is a method of expression that’s popular when you’re on the fringe. If I was middle-class and felt a lot of pain, I might wind up drinking or writing letters to the editor or beating the cat or trying to fight with my wife. But since I’m on the fringe, I became involved with a lot of artists.

The pain I feel is intense, excruciating. And I really haven’t suffered as much as a lot of people. I suffered when I was 14 when my mother and sister died under mysterious circumstances; I think that was easily the biggest moment of pain, and of course it colored me for the rest of my life. I know a lot of people who’ve really been through the mill. Rufus Hockenhull in Oakland photographs people who are down and out. He was in combat in Vietnam; he had to use a bucket to scoop up the remains of friends who were blown up; he saw a lot of people die. My next-door neighbor in New Jersey died in Vietnam. That kind of pain has stimulated me a lot.

I don’t want to complain too much, because I don’t think it’s appropriate. I think some middle-class mainstreamers actually suffer more than I do. They have a comfortable house (which is especially necessary for women and children), but they have the mortgage, they have a crummy job that they hate, they’re trapped.

Now, one thing about me is, I’m living what is probably a pretty natural existence in that I roam a lot and I’m like a lion or something — I go here and there, see the beautiful countryside. I have a good time, I’m completely alone, nobody’s bothering me. I see insanely, incredibly wonderful landscapes. I climb to the tippy-top of really tall mountains that are jagged, 13,000 feet in the air, looking down at incredible sights. I get a lot of good things to eat, plants that grow out there. I don’t often consider myself homeless — because my home is in the wilderness. I’m houseless, but that’s not the end of the world; it induces me to travel. I’ve hopped freight trains a lot. I go down to the seashore; I go to the mountains; I go out to the desert. It’s fun and it’s a good home, a very big home. So, I don’t suffer like a lot of people who just stay in one city. The cities, they’re just so grimy and gritty, all this concrete, all this filth, all these buildings — it’s depressing, it’s ugly.

A lot of homeless people live in a city and never get out of it. A house is more appropriate in a city because there’s no place to go that’s private. In the city, I try to sleep in my truck, but the police bother me; or I make coffee next to my truck outdoors, and the police unfairly bother me.

That’s another complaint. It breaks my heart to see police breaking the law. Many are more concerned with power than with the law. Supposedly these are the guys and women who uphold the law; but time and again for the last 30 years, I see police more concerned with power than justice. They’re supposed to follow the letter of the law! That’s what bothers me. It just completely erodes my respect for the law. If I see the police breaking the law, then I figure, “What the hell?! It’s all just about power!”

I don’t want to bad-mouth the cops too much, because they do handle some mighty rough customers who would just make me into a victim. But some injustices do come from them. There are other injustices too, like people who push you out of the way in the food line at the Emergency Food Project. There are times when I get hungry and just can’t get the food. There’s attrition; it wears you down.

Sometimes I write letters to the editor myself. But the truth is, there is this rage in me that comes up sometimes. I’ve got to do something about it, and, you know, draw or create art with toilet bowls or something. I’ve got to express it somehow, and actually I’m expressing it right now by being verbal. I’m sure it’s releasing some of the steam, the pressure.

But other people on the fringes have suffered a lot more than me. You think of these mothers with a couple of kids who are suffering and can’t get enough food, or get thrown out of their house or apartment. These are people who do not make art. They should — they should draw pictures or do something, because the expression would be very powerful. That’s why I like to get art materials together through grants and present them to people, and try to induce them to draw.

Injustice and deprivation stimulate. What do you do with it? Some people self-medicate. They drink or take cocaine, or something. I don’t. The only medication I have is coffee. So, instead, I’m involved in various forms of expression.

Some middle-class people are making out pretty good. But a lot of them are suffering big time. Lots of taxes, crummy jobs, mortgages. These people would also have some wonderful art to do, if it was in their culture. Someday I’d like to work on a bronze statue of a tired taxpayer working on his or her tax forms, piles and piles of paper, writing out a huge check to the government. Because I think these people are overlooked, and shouldn’t be.

I think the poor should attempt to build a coalition with the middle class, not fight them. We have so much in common; we’re all oppressed, we’re all hurting.

I see a lot of pain on the margins. Like, a 16-year-old boy dying of drugs. Alcohol takes a terrible toll. I see the results of that; I find it very disturbing. And that gives stimulus to my art, because I feel an intense amount of pain. I feel sorry for some people who are so lost.

Gino Alvarez: I’m at Peace with Myself

Gino Alvarez, long homeless in Berkeley, has a down-to-earth, open approach to life that is the opposite of the pseudo-sophistication of many cafe-loungers and shoppers. I often see Gino studiously work on a fine drawing right on the pavement amidst the bustle and noise of Telegraph Avenue. His art takes you away from the artificial, hectic conditions of the city, and expresses the natural beauty of birds and flowers. Gino’s carefully crafted drawings have a rough, virile charm, a sense of rugged spirit conveyed with a stark touch. He expresses basic, vital emotions and the spiritual meaning in nature and the wilderness that often get neglected in a city environment.

B. N. Duncan: A lot of artists living on the street don’t fit in with the official art-business world.

Gino Alvarez: They don’t! These stores around Telegraph won’t take my art to sell. Except Shambala. I can’t live on consignment — I’m homeless. I can’t wait. I can die out here. I’ve been out here homeless in Berkeley for 12 years, since 1983. I have a hard time getting even five dollars a day.

I tried all kinds of other work. I used to work in companies for other people who were above me. By doing that, what do I have to show? Nothing. I don’t even have a bank account. Now this way, when I do my art there’s no one above me. There’s just me. What I do, I do for me.

One thing I express is birds. What about the birds, man? And nature? I’ve been here a long, long time, and I don’t see nobody else doing it; they look at me drawing a flower and think I might be retarded.

In the unpeaceful city, I’m at peace with myself when I’m doing my art. When I’m not doing it, I’m very aware of the things wrong around me. You don’t know when somebody might go off; you don’t know when somebody might hit you with something. So I try to stay off the sidewalk, stay out of people’s way. I hang around a donut shop, sit there and draw. I have my work. I don’t want to drink a lot of alcohol and get stupid, and all that stuff.

Moby Theobald: History of the Starving Artist

Moby Theobald is an agreeable “good fellow” with spunk and initiative in working and helping others. Because he doesn’t have a forceful demeanor, many people would never pick up on his dynamic mind and spirit. He’s perky without being pushy. He likes to joke and hang out, but also has a persistent, active ambition.

Out of his homeless experiences, Moby has created a series of adult comic books with keen verve and incisive perspectives about being down and out. The series is titled, appropriately, Down and Out in Berkeley. His art communicates with a skillful, rough-hewn style, showing both the hard knocks of life and its hilarious side. His philosophical stories and his disappointing, harsh experiences bring laughter in abundance.

B.N. Duncan: I don’t see you producing mainly angry work, and I wouldn’t call your stories protest stories. But homelessness certainly gave you a subject for story-telling.

Moby Theobald:Yeah, before landing on the streets, I was doing little superhero spoofs, pretty lame stuff; and it didn’t really have any guts to it. When I hit the streets, my first thought was that it would give me something to write about — that it would let me explore myself a bit.

I think there’s sort of a history of the starving artist. There’s maybe two ways of looking at it. One is that when a person is poor, they kind of internalize. They turn away from the outside world, or they feel turned away by the outside world; so it maybe sparks their creativity. Another thing is that when you’re down and out, you have a lot more time on your hands; whereas if you were working a 9-5 job to keep a roof over your head and to keep the kids clothed and you’re part of the status quo, you don’t have time to paint or write or do art except as a recreation.

So people on the fringe have more time to develop their craft; they also have sort of a cocoon they can fall into, where they can really listen to themselves. That’s one of the reasons why you see creativity on the fringe — being able to listen to oneself.

Some people, their artwork or poetry is kind of angry. It’s directed at whoever they think has wronged them, which has a long-standing tradition too. You know, “Somebody kicked me out of their building! I’m going to write a nasty letter to the editor!” This reaction would, in different hands, be a poem or a painting, maybe a rendering of this horrible person doing wrong. I think everybody feels somewhat persecuted, and the further down you go, the more persecuted a person feels — or maybe the more often the person is persecuted. Because everybody who gets kicked in the butt is kicking somebody else in the butt; and so, the further down you go, the more kicks in the butt that person gets. So I think a lot of it is a response to having been shunned or treated badly or kicked out. Charlie Chaplin said, “If it happens to you, it’s tragedy. If it happens to someone else, it’s comedy.”

I think people need to have bad things happen to them just to give them something to write about sometimes. If you write about good things happening to you, people will think you’re bragging. As long as you stress the negative in your life, then people will console you and appreciate you. They’ll go: “Wow! That’s great! I have bad things happen to me too.” People like to get together and commiserate. In the artists’ community, a lot of griping and commiserating is probably a healthy relation with the different artists.

I’ve been thinking lately that in order to have something interesting to write about, one has to suffer. Which I think is a terrible philosophy, because it means that if you have to constantly have terrible things happen to you in order to have something to write about, you’re never really going to be happy. You’re never going to really achieve success because you’re going to be afraid of it. “Suppose I become successful? Then I’ll have nothing to write about.” It’s sort of a trap.

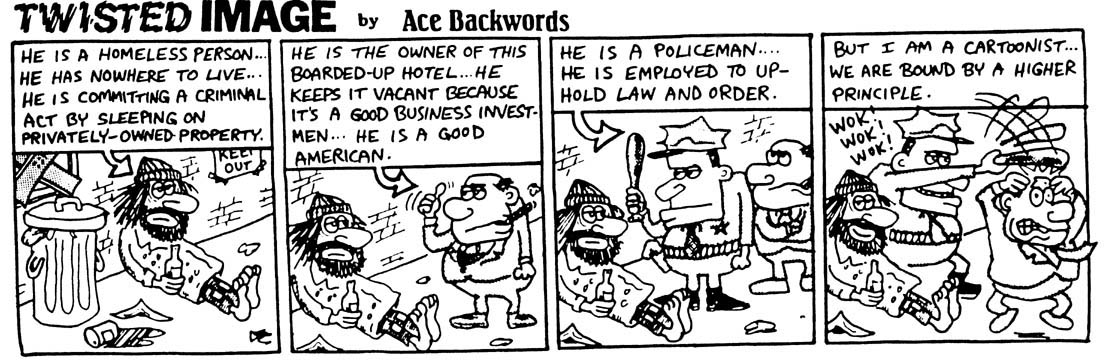

Ace Backwords: Humor and Righteous Indignation

Ace Backwords was once homeless and never forgot it as he eked out a bare living apart from the social mainstream. He is an original, hot-blooded man, outstanding in the clarity of his thinking and speech. He’s a doer — determined and resourceful. He likes people, but is tormented by his critical observations of society and the human condition. Sometimes he’s sociable; at other times, a recluse. Ace has a sense of humor mixed with righteous indignation; he’s a frustrated romantic, a satirist driven to throw critical barbs. He’s restless, churned up inside and has strong reactions to a life that feels uncomfortable. He always stays interested in subjects that give his life meaning and fuel his work.

Ace has built up a very impressive and varied body of work. Among his activities are cartooning, writing, publishing, documentation and music. Key features in his work are parody, satire, disillusionment and criticism on the one hand; and, on the other, a warmth and heat that comes from the heart. His achievements include hisTwisted Images book and publications; his many comics; the Telegraph Avenue Street Calendar co-authored with B.N. Duncan; and a CD record, Telegraph Street Music, a recording of wild, creative street musicians, along with a magazine profiling the performers.

B.N. Duncan: I remember a long time ago you drew a comic strip while you were living on the street that got into the Berkeley Barb when it was still around. Why did being marginalized result in art?

Ace Backwords: It seems like valid art is arising everywhere. My impression is that there are artists everywhere, creating stuff all over the globe. Berkeley does attract a fair share of artists and free spirits.

People on the street scene don’t have much. You can’t afford a lot of entertainment, so sometimes we have to entertain ourselves. Rather than go watch professional drummers, we’ll have a drum-circle and just beat on the drums ourselves. We’re out there on the street together, so we sing and make songs and paint our pictures and create stuff ‘cause it’s an outlet that is available. It’s one thing they can’t take away from us. It’s something that’s available to anybody, rich or poor. Whereas we can’t go off yachting, we can paint a picture.

I think the urge to create art is therapeutic. It’s healthy to express certain things about yourself that maybe are off. If you have a problem, it’s good to work it out on paper and communicate it to other people, just to get clear about it.

That’s part of the motivation; there’s an underlying sense of reaching out to other people, especially about the harsh conditions that people face out here. I think it’s good to remind people in the mainstream that we’re out here suffering in bad conditions. I think that’s one of the prime functions of Street Spirit — so people don’t forget, and so some people will respond and will help. Some of this is an appeal for help.