by Lydia Gans

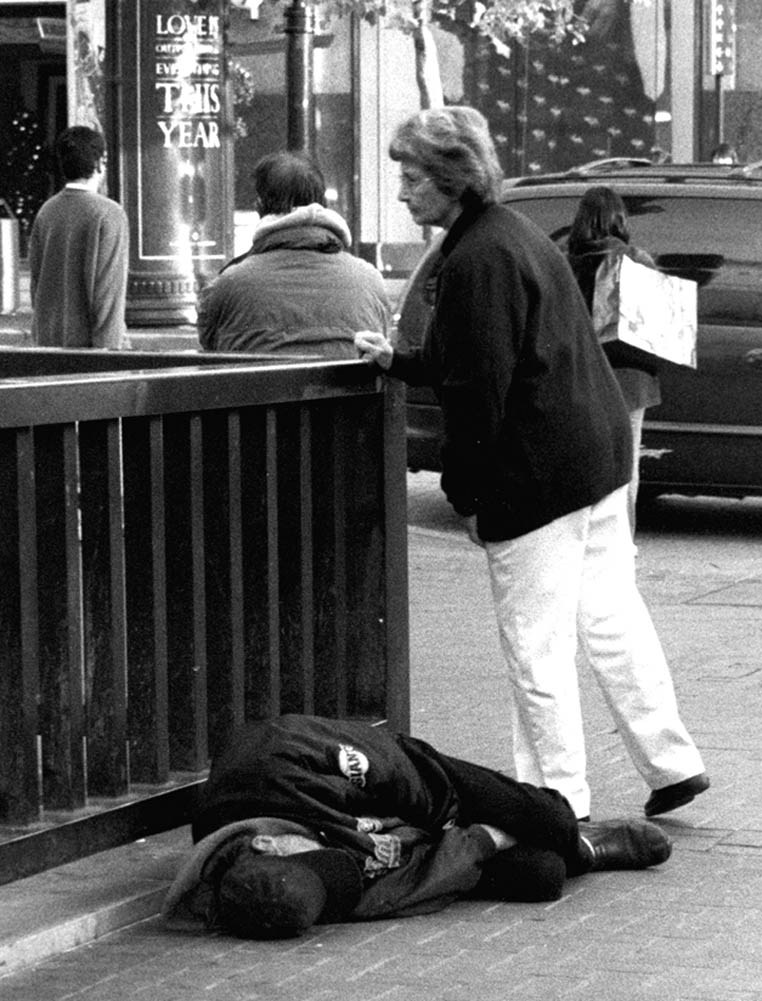

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n my photography, I have been focusing on people who are not in the public eye, people who are more likely to be unseen or ignored, but who sometimes have to struggle to survive under great handicaps. I have photographed and written about children and adults with disabilities, elderly people, and people who are homeless and destitute.

My photographs are of people I sincerely care about. In the English language we talk about “taking” a picture. I prefer the German where the operative verb is “making” a picture. I am not taking anything from the people I photograph. They give me their trust and I give them my respect and a chance to tell their stories, a chance to be seen and heard.

My mission as a photographer is enhanced by other activities which all stem from my commitment to social justice. For many years I’ve been a family service volunteer with the Red Cross. We help people get back on their feet after a disaster.

In Oakland, house fires are almost daily occurrences. Poor people, people living in substandard housing, are the victims. They lose their few possessions, the children are traumatized and entire families are left homeless. Not infrequently, some helpless person, a child or someone elderly or disabled, dies. The emergency help that we are able to give them is barely enough for them to catch their breath.

I am constantly amazed and awed at the strength and resourcefulness, especially of the mothers or grandmothers, in holding things together. And I value the association with my fellow Red Cross volunteers, people like me who are retired or working part time and are driven by the same desire to help the victims of misfortune, and have respect for their human dignity.

Besides photography, my most satisfying work and meaningful association is with the Food Not Bombs collective in Berkeley. We prepare a daily meal for people who are homeless, or poor, or just passing by and are hungry. Unlike most churches and charities that run soup kitchens, where there is a distinct separation between the givers and the receivers, we see ourselves as sharing a meal with the community.

There’s a political message here, too: the fact that there is plenty of food out there but the economic system is such that vast amounts of food go to waste. While some have too much, others go hungry. In the eight years that I’ve been part of Food Not Bombs, I’ve cooked and eaten together with people who share my vision of a more just and peaceful society, people who are activists in the cause, and people who are victims of the system just trying to survive.

My first solo photography show consisted of images I took on my travels in many diverse parts of the world. I didn’t photograph scenery or buildings — there are always plenty of postcards available to remember those by. What interested me, what I care about most, and still do, is the people I encountered along the way.

In my introduction to the show I wrote: “Beyond the glorious feeling of freedom that happens when I’m on the road, there is a profound recognition of kinship with all peoples — a realization that we have far more in common than we have separating us. I am that mother, worrying about her child’s future, in Mexico, in India, in Norway. I have the same hopes and dreams of a fulfilling life as the women in central Europe or in central Asia. I appreciate and identify with the struggles for an equal right to the good life carried on by the women of Cuba or of Canada.”

I haven’t been traveling abroad as much lately, but my sense of identification with the struggles and the dreams of people is as intense as ever. Now the people I am connecting with are right here in my neighborhood. Some are people making news, participating in demonstrations for peace or social justice. Others are the less visible people who are disabled or poor or homeless and whose images and stories need to be brought to public attention.

I came to photography late in life, or rather, came back to photography. When I was a teenager growing up in New York City, my father gave me a fine camera he had managed to bring with him from Europe. Influenced by the work of photographers like Alfred Stieglitz and Dorothea Lange, I wandered all over the city, photographing kids playing in alleyways and old men sleeping on park benches. I left home without the camera, and it was more than 30 years before I seriously picked it up again to once more document the world around me.

Mine wasn’t a typical American childhood. I was born and spent my first years in Germany. Hitler had stolen the election and brought the Nazis to power, and the storm which grew into World War II and the Holocaust was gathering momentum.

Everyone who was vulnerable tried to leave, though it wasn’t easy to find countries that welcomed refugees. To come to the United States required a sponsor here who would agree to take responsibility for the new immigrant. We were lucky. My father knew people here who provided the necessary affidavit and allowed us — my mother, father and me — to camp in their home until we could get established in a place of our own.

As soon as we were settled, my parents in turn sponsored other families who were fleeing from fascism, housing them and helping them get a start in the new country. I grew up with a constant flow of people coming in and out of our apartment, coming from different backgrounds with different problems, speaking various languages, all trying to learn English and adapt to America. Most arrived with nothing but the desire to start a new life in safety and freedom.

That’s the immigrant experience, and it’s pretty much the same for victims of any kind of inhumanity, be it terrorism or starvation or war. It gave me a view of the world that appreciates resourcefulness in the face of great stress. It taught me to accept and understand the diverse ways people cope with life. I can appreciate those same qualities in the people I encounter in the course of the work I do now.

I traveled a lot, and worked or studied abroad; but, except for photographing family and friends, I left the camera at home. I wanted to experience life directly, to absorb the world with my senses and store it in my heart and my mind.

Traveling with a camera is an entirely different experience. You are looking at the world with the idea of creating images to share with other people. What you see is filtered through a part of the brain that figures out the message you want to put out and how best to present it.

Later, I picked up the camera again and began to focus on that as I realized that I had messages that I wanted to bring to the world. That first exhibit of portraits was followed by several shows of photos I took while participating in a sister city project in Nicaragua.

As I started moving out of academia, I took some classes in photojournalism, converted half my kitchen into a darkroom, and embarked on my new life work as a photojournalist and documentarian.

I think of photojournalism and documentary photography as somewhat different processes. The photojournalist takes pictures of events and actions to illustrate the accompanying articles. For me, photojournalism is a lot of fun. I love photographing demonstrations, marches, housing takeovers and such. I would probably be participating in many of these activities anyway. As long as one masters the camera, it’s not hard to get good pictures. The key is to be there, to be very aware, to be very conscious of everything that’s going on, and to be right in the middle of it!

For me, documentary photography is a different and very satisfying work. It is telling a story, in pictures and words, of an aspect of life that wants telling. I have published a book of documentary photography on people with disabilities.

There are many journalists covering suffering in the world. It is news when people die from mortar attacks or suicide bombers in the Middle East, or when the number of homeless panhandlers in the city becomes uncomfortably obvious. But it takes something more than a feature story, to be quickly followed by another subject. It takes some sort of deep commitment to move people enough to care and to make a change.

I most admire and identify with the great photographer Sebastiao Salgado, a Brazilian and former academic economist. His work shows his deep love and concern for the lives of people all over the world. He has made wonderful images of people at play and at work, of people celebrating and suffering.

His latest, most powerful and deeply moving work is a set of hundreds of images, titled “Migrations,” depicting people who are dispossessed, people who have been forced by politics or economics to leave their homes and wander about in search of a better life. The photos are not pretty. They are painful to contemplate, but they are terribly important. The entire exhibit was shown in Berkeley last year.

Salgado writes, “More than ever, I feel that the human race is one. There are differences of color, language, culture and opportunities, but people’s feeling and reactions are alike. People flee wars to escape death, they migrate to improve their fortunes, they build new lives in foreign lands, they adapt to extreme hardship. Everywhere, the individual survival instinct rules. Yet as a race, we seem bent on self-destruction…. Perhaps that is where our reflection should begin: that our survival is threatened…. We hold the key to humanity’s future, but for that we must understand the present. These photographs show part of this present. We cannot afford to look away.”

My photographs, too, show a bit of the present; and it is my fervent hope that society will not look away.