by Carol Denney

[dropcap]C[/dropcap]lassical guitarist Philip Rosheger died on December 4, 2013, of complications following heart surgery. His family and friends know how deep a loss this represents musically and personally, and a larger community of those who knew him only through his music will share in their bereavement. But everyone might benefit from knowing more about his life and the circumstances through which he made music out of even the most humbling moments.

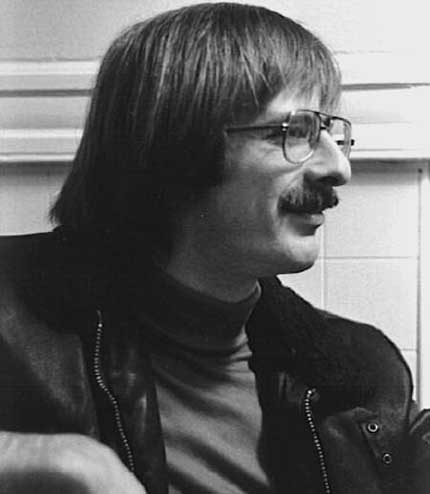

Born in 1950 in Oklahoma, Philip Rosheger’s musical study began with piano lessons, then quickly moved on to master guitar lessons with Andres Segovia on full scholarship from the Spanish government. He was the first American to win first prize in the International Guitar Competition, an honor he won in 1972 when he was only 22.

He was on the faculty of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music from 1975 to 1978 and worked at Sonoma State University from 1979 to 1989, in addition to performing and giving master classes.

Philip also played locally in restaurants, pizza parlors, nursing homes and on the street. He used to laugh that he possibly shipwrecked his reputation by doing so. The world of classical music was peculiar, he would explain to those who would listen. It had a snobbery that made him bristle.

He told me once about how booking a national tour the usual way forced him to criss-cross the nation back and forth repeatedly through various time zones and rush from airport to concert hall and back. Minimizing “downtime” maximizes money, the agent’s logic went. Cramming as many gigs as possible into a short space of time saved on hotel costs, and spreading the gigs wildly from one end of the country to the other minimized taxing the same draw.

This is musician-speak, and I’d heard it as a young child from the jazz musicians my parents knew from the Los Angeles area in the 1950s and 1960s. One hitch in the weather, one difficulty at one airport, one flat tire could jeopardize an entire tour stacked back-to-back with barely enough time to travel between them. It was a harrowing life, especially without family or the comforts of home.

It was so soulless and exhausting for Philip that he insisted that his next tour be booked with logic other than financial so that he could adjust his body, meet the people in a region, take a look at the countryside, and enjoy the journey. For Philip, every moment offered an opportunity to make a real connection.

If you were willing to wait respectfully until the end of a composition, Philip would tell you its composer and its history. If the composition were his own and he had his folios nearby, he would show you some of the decisions he’d made musically along the way and talk composition.

One of my favorite moments was in what we called Ho Chi Minh Park in Berkeley, trading tunes and goofing around with his friend and well-known classical guitarist Michael Lorimer. I remember thinking how wondrous it was, the town of Berkeley, where two such esteemed musicians could be heard by just wandering through a public park.

Philip loved being able to evoke a sense of wonder in people who might have little musical background and zero interest in what can be a cut-throat classical competition. The sheer love of music transported him entirely and he could always tell when people had taken the journey with him.

One of his students, Dan Winheld, wrote this about the experience of taking a lesson with Philip: “It was by far the best single guitar music lesson I have ever had, if not one of the best private music lessons ever — and I have studied with masters from Alirio Diaz to Hopkinson Smith, and enough others in between. Phil spent over three hours or more teaching me about tango, its history, Piazzolla, Leo Brouwer, tone production, and more while seated on the floor in half-lotus position — all the while demonstrating with incomparable ease and mastery on his guitar, playing with an authority, expertise, and more tone color than I have heard any classical guitarist pull from the instrument.”

But Berkeley changed. Philip fought an eviction from his apartment for a long time, knowing that the loss of his rent-controlled apartment would exacerbate an already precarious financial situation. He had no buffer against the rapacious rent hikes going on around him except a wealth of friends’ generosity.

At one point, he decided that he would leave the United States, with its obsession with consumerism and seeming disdain for the arts and artists, and return to the Europe of his youth, where his talent and facility for language and music found easy welcome. But Europe had changed, too.

The new, terrorism-obsessed world now had policies restricting foreigners’ ability to work, requiring citizenship papers, forbidding busking, etc. He traveled from country to country trying to find the harbor that had once existed for artists, and finally gave up, accepting a plane ticket home from friends.

Philip was right about Europe in the 1960s, according to the conversations I remember of touring jazz musicians, such as Herb Geller, who finally gave up touring the states. The difficulties for artists in the states compared to the reception elsewhere in the world was often a topic of conversation at my house, and my parents could only apologize for the overt racism of Los Angeles police and the general disrespect toward artists.

But Philip hadn’t banked on a post-911 world where the American disdain for art as frivolous and expendable would infect European culture as well, as he saw it. His more recent years after his return from Europe were difficult, but he continued playing and attempting to reconstruct folios of original compositions he’d lost during his travels, until a stroke in 2013 severely affected his playing.

Philip and I spent long hours on the phone lamenting the unwillingness of local musicians to organize on their own behalf. When the Solano Merchant Association decided to save money by discontinuing payments to Solano Stroll musicians, Philip Rosheger was one of the few musicians who immediately understood and supported refusing to play, a stand one takes at the risk of being blackballed. He scolded musicians who played for free, thus allowing often wealthy business owners to short-change musicians and artists and running working-class artists entirely out of the game.

His difficulties here were in sharp contrast to a trip to Mexico only a few years ago for a series of performances, where his enthusiastic welcome was overwhelming.

As his sister Carla put it, “Philip and I talked by phone at length on how he felt about the incredible reception he received in Mexico in stark comparison to the USA. He was truly amazed, humbled and honored by the fact that the Mexican musicians continuously called him Maestro. I told him, ‘That’s because you are a Maestro, Philip.’ I know this journey gave Philip renewed passion for continuing his music the way he thought he should here, no matter the sometimes negative fallout.”

But both of us knew that what may seem like end-times for musicians are not musicians’ fault. In the 1940s in San Francisco, for instance, any local bar worth its salt had a piano, a piano player, the best musicians they could find to play best-loved tunes and competed for business with their music against the bar band down the block — a perfect recipe for keeping good musicians working at least consistently, if not well paid.

Then came canned music — the jukebox at first, then later the attitude that somehow playing music live in public was either rude or wrong. The generation that grew up hearing music come out of boxes instead of played live often has no objection to brutally repetitive synthesized beats and little awareness of technology’s cold effect on working musicians already ill-treated by a commercially driven music industry now on the rocks.

Philip was completely captivated by the marriage of tones and the collision of rhythms. We talked for hours about music and politics and the changes we’d seen over our decades of playing. We watched as dozens and dozens of our friends put down their instruments, hammered by irate roommates, time and family constraints, or physical ailments. But we kept playing.

One of Philip’s joys in the last few years was finally finding a place to live in an apartment in Oakland where a musician, a horn player, lived in a nearby unit. Philip told me he knocked on the man’s door, and when the man opened the door the man immediately began to apologize for playing. Philip laughed and said, no, no, he had only knocked on his door to thank him for the music and tell him how much he loved hearing him play.

Philip’s family had a small private memorial after his passing, but is planning a public memorial concert this spring in celebration of his life and music. A fundraising effort has been set up on a website called GoFundMe to defray costs and assist with efforts to produce recordings of some of Philip’s work so more people will have a chance to hear and appreciate his unique compositions.

Many of Philip’s friends have written moving tributes on the site to the man who changed either their playing or their understanding of music forever, or both.

Philip’s brother Michael remarks on the site, “When I think of Philip, I find solace in the words of Will Durant; ‘In all things I saw the passion of life for growth and greatness, the drama of everlasting creation. I came to think of myself not as dance and chaos of molecules, but as a brief and minute portion of that majestic process.’ I can think of no better words to describe Philip’s philosophy on life, except to say, ‘follow your passion.’”

Philip’s family put “Follow your passion” on the urn that holds his ashes as an expression of the life which took Philip all around the world. As he traveled, Philip opened thousands of hearts to not just music, but music’s historical context and its necessity as part of what keeps us connected and makes our lives seem fresh and new every moment. Philip knew that music was not expendable, that it was often the key straight to the heart, and he loved to make that connection in a world where stopping for a moment even to enjoy one of the world’s most highly acclaimed compositions has somehow become a difficult thing to do.

That we are all brothers was a given to Philip, who couldn’t understand how Berkeley ‘s priorities had become so confused that it was systematically pricing and pushing out the working-class artists who were his friends and neighbors, and the people who managed against all odds to share what little they had on the streets.

“He was a musical angel,” reflects Suzanne Sastre, one of his oldest friends. “He was not pretentious, though he could have been. His head was in the clouds or somewhere magical. He loved to have fun, he loved to chat, and he was very kind.”

The man who would have given anyone the shirt off his back left very little behind him except that same starry look in the faces of those who knew him, heard him, and loved him. His guitar will go to one of the musicians who played his compositions, and his music will be treasured as long as we can hold on to what is so precious in this world: the music that celebrates with such perfection what is most beautiful about us as human beings, creatures of unparalleled imagination and joy, honored and loved by a caring community.