by Paul Boden, WRAP

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he Quality of Life ordinances enacted in cities across the nation to outlaw and banish homeless people from certain areas are our contemporary version of the vagrancy laws that have been with us for centuries. In the South, they were used to force freed slaves back to the plantation. In the North, they were used to instill a Protestant work ethic in indigent whites.

This compulsion to control labor and separate the “worthy” from the “unworthy” is deeply ingrained in our culture and institutions. By drawing comparisons between today’s anti-homeless legislation and three specific episodes in U.S. history, we hope to shake the complacency surrounding our present civil rights failures. If we don’t, future generations will surely ridicule our hypocrisies as we do those who came before us.

A Wolf in sheep’s clothing

How ugly is too ugly? How dark is too dark? How poor is too poor? These perverse questions were at the heart of ugly laws, sundown towns, and the Bum Blockade — unconstitutional predecessors of today’s Quality of Life ordinances.

Unlike the above policies of segregation that brazenly named the objects of their scorn — “masterless men,” “cripples,” “Negroes,” and “Bolshevik bums” — today’s vagrancy laws are dressed up in post-civil rights legalese. By targeting behaviors like sleeping, lying down, sitting, and urinating in public, Quality of Life laws attempt to sidestep the protection afforded by the Civil Rights and Americans with Disabilities Acts.

In reality, this legal fine-tuning is the same old wolf in sheep’s clothing. The ableism, racism, and classism that underwrote yesteryear’s ugly laws, sundown towns, and the Bum Blockade can be found in today’s Quality of Life ordinances.

The words of Martin Luther King from a Birmingham jail ring as true now as they did in 1963: “We will have to repent in this generation not merely for the hateful words and actions of the bad people but for the appalling silence of the good people.”

Many liberals and progressives, when aware of them, look back at past exclusionary practices with scorn and shame, yet they are silent when it comes to current battles over public space, freedom of movement, and civil rights. We bring the following history to public attention so that we may wake up to what Quality of Life ordinances really are.

What follows draws heavily on the scholarship of Susan Schweik, author of “The Ugly Laws: Disability in Public,” James Loewen, author of Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism, and Hailey Giczy, “The Bum Blockade: Los Angeles and the Great Depression.”

The Ugly Laws

Beginning in the second half of the 19th century in San Francisco, other cities, including Portland, Chicago, Omaha, Columbus, Cleveland, and Denver began enacting “unsightly beggar ordinances.” These ordinances came to be known as “ugly laws.” Their main purpose was to control disabled people’s freedom of movement and speech in public space.

Chicago’s 1881 ordinance read: “Any person who is diseased, maimed, mutilated, or in any way deformed, so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object, or an improper person to be allowed in or on the streets, highways, thoroughfares, or public places in this city, shall not therein or thereon expose himself to public view, under the penalty of a fine of $1 [about $20 today] for each offense.”

The laws specifically proscribed a person from exposing a disability in public space for the purpose of begging. They were one of the country’s first panhandling laws. A large percentage of ugly laws had “poorhouse clauses” that banished disabled people to jails or almshouses if they couldn’t pay the fine.

Susan Schweik writes, “The crude elements of ugly law may be broken down roughly as follows: the call for harsh policing; anti-begging; systemized suspicion set up to winnow the deserving from the undeserving; suppression of acts of solidarity by and for marginalized urban social groups; and structural and institutional repulsion of disabled people, whether by design or by default. None of these have disappeared since the demise of formally enacted unsightly beggar ordinances.”

The last known arrest stemming from an ugly law happened in Omaha only 36 years ago. Ugly laws attempted to accomplish what cities are now aiming to achieve with sit/lie bans and anti-panhandling ordinances: to reinforce social boundaries and marginalize those considered “unsightly” in the newly preserved historic downtowns of the closed city.

Sundown Towns

In response to the upheaval in “race relations” caused by Reconstruction and the Great Migration following the Civil War, white towns from Florida to Oregon barred African Americans and other despised ethnic groups like “Jewish, Chinese, Japanese, Native, and Mexican Americans” from entering them. One such town in Illinois went by the name “Anna,” short for “Ain’t No Niggers Allowed.”

Known as sundown towns, these white supremacist redoubts got their name from the customary signs placed at the entrance of town warning targeted ethnic groups “not to let the sun set on you” within city limits. Government complicity, vigilante justice, and race riots backed these threats.

Lesser known than their southern counterparts — Black Codes and Jim Crow — sundown towns were far from being a marginal phenomenon. There were thousands of them and many could be found in elite suburbs right outside of metropolitan areas like New York City and Chicago.

James Loewen concludes, “From the towns that passed sundown ordinances, to the county sheriffs who escorted black would-be residents back across the county line, to the states that passed laws enabling municipalities to zone out ‘undesirables,’ to the federal government — whose lending and insuring policies from the 1930s to 1960s required sundown neighborhoods and suburbs — our governments openly favored white supremacy and helped to create and maintain all-white communities. So did our banks, realtors, and police chiefs.”

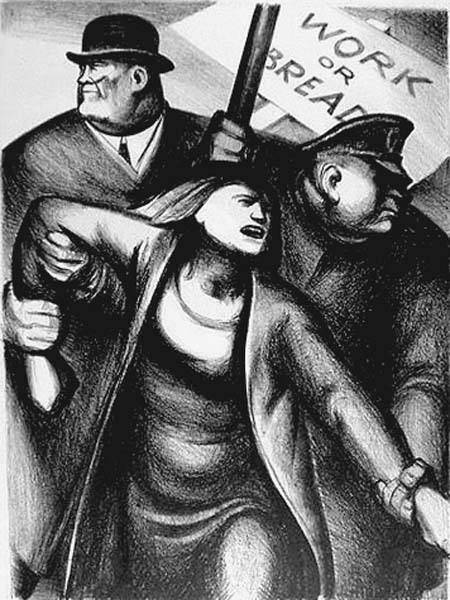

Lithograph, 1934, by Jacob Burck, courtesy of M. Lee Stone Fine Prints

The Bum Blockade

“Bolshevik bums.” “Won’t workers.” “Migratory criminals.” “Two-legged locusts.” Los Angeles Police Chief James Davis hurled invectives like these at Dust Bowl refugees in the pages of The Los Angeles Times throughout 1935. Like contemporary Quality of Life campaigns, Chief Davis linked the influx of “Okies” with crime and financial loss to scare up support for his “Bum Blockade.”

The Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce did its part by stoking nativist resentment. They reported that migrants were costing taxpayers millions of dollars a month in state relief — aid that many struggling Californians were unable to receive. The public relations campaign around the Bum Blockade fueled a nasty parochialism that drove a stake between segments of the working and unemployed poor, scapegoating those from other places for the high unemployment and long welfare rolls wracking the state.

In 1936, Police Chief Davis took matters into his own hands, enforcing an aggressive fingerprinting and deportation campaign for anyone arrested on vagrancy charges in Los Angeles.

He also took the extraordinary measure of sending well over 100 officers to the borders of California and Oregon, Arizona, and Nevada. Officers set up blockades to question incoming travelers if they had money or work. If they didn’t, they were told to either go back to from where they came or face hard labor. Around the same time, California put an anti-Okie law on the books that made it a misdemeanor to bring an “indigent person” who wasn’t a resident into the state.

Such measures directed at “Okies” spurred John Steinbeck to write in The Grapes of Wrath, “Well, Okie use’ta mean you was from Oklahoma. Now it means you’re a dirty son of a bitch. Okie means you’re scum.”

The Bum Blockade eventually failed because it was too expensive and the Supreme Court struck down California’s anti-Okie Law as a violation of the Interstate Commerce Clause.

Hailey Giczy writes, “In order to preserve the homogeneity of Los Angeles’ ‘imagined community’ of wealthy and culturally advanced Anglo-Saxons, tactics used to exclude racial groups were employed to attack class groups, raising exclusionary sentiment in Angelinos which fueled a fear of moral and aesthetic degradation.”

An Emphatic “No!”

Vestiges of the ugly laws, sundown towns, and Bum Blockade persist in our current Quality of Life ordinances. They create second-class citizenship, criminalize poverty and disability, close public space, and encourage vigilante justice. The corporate media arouses fear and dehumanizes the poor and disabled, business groups like the Chamber of Commerce demand the state protect their interests, and police overstep the constitutional limits of their power.

Throughout this sordid history, courageous people have stood up and declared an emphatic “no!” to policies that exclude, segregate, and deny universal human dignity. Society can learn much by highlighting the work of those carrying on this tradition of resistance, those who today are demanding social justice.

Paul Boden is the organizing director of the Western Regional Advocacy Project (WRAP).