by Paul Boden

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hat images do the words “quality of life” bring to mind? A peaceful beach? A beautiful park? A farmer’s market full of healthy produce? In the realm of policing, the phrase “quality of life” carries different connotations. It means a veteran getting hauled in for sleeping on the sidewalk, a homeless woman being prohibited from resting on a park bench, or even brutal scenes of police repression in the cities of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Fresno.

For poor, homeless, queer, transgendered, and disabled people, “quality of life” is a zero-sum game. It means someone else’s life is better only if theirs is worse. It also means no begging, no sitting or lying on public benches or sidewalks, no congregating in public space, and no sleeping outside.

In this context, “quality of life” is an array of ordinances being used against people deemed “abnormal” or “undesirable,” especially in gentrifying areas. Quality of Life campaigns have been driven by the concerns of Chambers of Commerce, Business Improvement Districts, and residents uncomfortable with the unsightliness of extreme poverty, especially middle-to-upper class whites.

The heavy-handed tactics carried out during police raids against homeless people are extreme expressions of the daily harassment visited upon those who have to struggle with poverty, addiction, mental illness, and disabilities in open public view because they lack basic amenities such as housing. These tactics help the police clearly demarcate urban boundaries and enforce who belongs where. They’re part of a social system where welfare and punishment have become almost indistinguishable.

Quality of Life laws are based on the “Broken Windows” theory, first popularized in an influential 1982 Atlantic Monthly article written by James Q. Wilson and Edward Kelling. The article reflected the ascendant conservative ideology that New Deal and Great Society programs had turned the United States into a “nanny state” that reinforced the laziness and criminality of the lower classes, especially people of color. This is the theory’s dubious starting point.

The premise of the Broken Windows argument is simple: it is necessary to come down hard on the “disorderly” (e.g., homeless panhandlers, drunks, prostitutes, and rowdy youth) to discourage more serious criminals from taking over a neighborhood. This was to be done by saturating selected areas with beat cops that have the “discretionary authority” to not only respond to actual crimes, but to “manage street life.” These tactics go by the various names of zero tolerance, order maintenance, and broken windows policing.

Wilson and Kelling write: “The unchecked panhandler is, in effect, the first broken window. Muggers and robbers, whether opportunistic or professional, believe they reduce their chances of being caught or even identified if they operate on streets where potential victims are already intimidated by prevailing conditions.”

“Tough on Crime” advocates saw Broken Windows as a panacea to the problems facing their cities. The cumulative effects of economic stagnation, growing inequality, unemployment, rampant privatization, and government neglect were ravaging urban centers.

The first to apply it were New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and his Police Commissioner William Bratton. In 1994, they put forward Police Strategy No. 5: Reclaiming the Public Spaces of New York. Giuliani and Bratton made their careers off exporting this model. Giuliani created a consulting company and Bratton took jobs in other major cities such as Los Angeles.

In recent years, activities associated with being homeless became the most glaring signs of disorder that needed to be eliminated. As a result, the problems faced by homeless people were transformed into a criminal justice issue. Today, more than 50 cities have passed laws that prohibit sitting or lying down in public places and 100 localities have passed some form of anti-begging ordinance.

To bolster Quality of Life policing efforts, Business Improvement Districts have hired private security guards to monitor and patrol public space with scant oversight to limit civil rights violations.

Consequently, public funds are being redirected from social services to homeless courts, jails, and prisons. So much so that in 2007, a public defender in Los Angeles told the Daily Journal on the condition of anonymity: “It’s not abnormal for the DA to have a policy. But this policy is about targeting the homeless in that area because the city is redeveloping that area. It’s a policy to get people off the streets and into state prison, jumping right over rehab and jail.”

Quality of Life campaigns have been credited for cleaning up and making business, entertainment, and shopping districts more enjoyable for their intended users, namely tourists, shoppers, and concertgoers. In New York City, for example, the campaign was so successful that only one homeless man remains in Times Square, but at the same time homelessness in the city was up 34 percent.

So the question must be asked: Do these ordinances actually work or are they “politically successful policy failures?” Who exactly do they work for and at what cost for society as a whole? Do the ends justify the means? Or are we once again developing a repertoire of exclusionary mechanisms that further tarnish our country’s claims on freedom, equality, and justice for all?

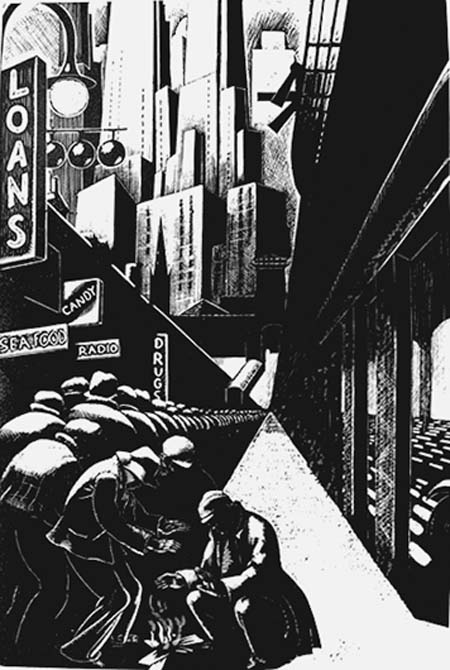

“Bread Line.” Wood engraving by Clare Leighton

Courtesy of M. Lee Stone Fine Prints, San Jose

There is no clear evidence that Quality of Life campaigns have seriously reduced crime. In his book Illusion of Order: The False Promise of Broken Windows Policing, University of Chicago law professor Bernard Harcourt calls attention to a Harvard study in which the authors conclude that “the current fascination in policy circles on cleaning up disorder through law enforcement techniques appears simplistic and largely misplaced, at least in terms of directly fighting crime.”

In the pursuit of “safe,” “sanitized,” and “livable” cities, we’re systematically stripping people of basic civil and human rights and banishing them beyond the realm of human decency. By reactivating or expanding the application of archaic vagrancy laws, we’re criminalizing the basic necessities of living and keeping in existence a disgraceful system of second-class citizenship. Nightsticks and jail time cannot address the lack of housing and services that put millions of people on the streets in the first place.

Even Wilson and Kelling concede that: “Of course, agencies other than the police could attend to the problems posed by drunks or the mentally ill, but in most communities especially where the ‘deinstitutionalization’ movement has been strong — they do not.”

They go on to raise concerns about equity: “How do we ensure that age or skin color or national origin or harmless mannerisms will not also become the basis for distinguishing the undesirable from the desirable? How do we ensure, in short, that the police do not become the agents of neighborhood bigotry?… We are not confident that there is a satisfactory answer except to hope that by their selection, training, and supervision, the police will be inculcated with a clear sense of the outer limit of their discretionary authority. That limit, roughly, is this — the police exist to help regulate behavior, not to maintain the racial or ethnic purity of a neighborhood.”

So, why have police become our society’s primary service providers? Aren’t other agencies better trained to deal with health, social, and economic problems? Our society must take a look at the “long and unbecoming” history of other exclusionary social policies carried out in the name of “regulating behavior.” Histories that should make us think twice about the police’s ability to provide safety for everyone.

We hope that looking at Ugly laws, anti-Okie laws, and Jim Crow laws will give us the distance and perspective we need to illumine our own blind spots and democratic failings. The fact of the matter is, we can only police the gross inequality riveting our society for so long.

Paul Boden is the organizing director of the Western Regional Advocacy Project (WRAP). This series analyzing the Quality of Life movement is a collaboration between researcher Casey Gallagher and WRAP.