by Linda Ellen Lemaster

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he Santa Cruz Eleven have become political scapegoats for a property crime, and Occupy Santa Cruz finds itself an unlikely eye in the middle of this storm.

It all started at 75 River Street in Santa Cruz, a block away from the Town Clock, when an empty Wells Fargo bank building was occupied last winter, and activists seemingly dreamed it into new life as a haven for a community made flesh.

Breaching our civilization’s private property taboo is no joke, yet the arms of the state have set upon the wrong people, indicting 11 journalists and activists who visited the building occupation at 75 River Street, instead of seeking out those who actually were involved in the alleged “property crimes.” At this writing, the police and the district attorney’s office are still barking up the wrong tree, and already their judge is nearly howling that “someone must be responsible.”

The transformation of the vacant building at 75 River Street by “Anonymous Autonomous,” who claimed to be Occupy Santa Cruz supporters, began Nov. 30, 2011. A momentary celebration of inclusive life erupted for three days — a cooperative experience of a caring culture. A spontaneous and collaborative dance of activity had briefly displaced the more ponderous civic reality.

Even in the midst of our country’s recession, upholding property laws often will receive more public support than will people’s survival. In particular, this political struggle unfolds because police created the Santa Cruz Eleven by indicting defendants almost randomly, in a witch-hunt meant to find — or perhaps even to invent? — someone to hold responsible for opening the long-vacant bank building to the public.

Anonymous Autonomous

Anonymous Autonomous is not a subgroup of Occupy Santa Cruz, and it is not a local club or gang. Apparently, it’s a name somewhat inspired by the Occupy Movement’s coast-to-coast dialogue on “diversity of tactics.” Let’s just call it “AA” here, undefined, and with apologies to Bill.

AA helped broadcast the planned March Against Foreclosures; and AA was ready for company, with a huge welcoming sign unfurled from the roof of the bank building, and front doors open, when this march stopped at 75 River Street.

The occupation of 75 River Street had sprung to life despite short-sighted planning by AA building liberators, despite internal Occupy Santa Cruz conflicts and flame wars about methods and identity immediately following the building takeover, and despite a Homeland Security fashion show that bared its steel teeth for a moment while forcing everything back into a dolorous status quo designed to keep the 99% and the 1% believing themselves apart.

Yet the Anonymous Autonomous activists were nowhere in sight after the police came by to monitor the protest and then left that first night; and were still nowhere to be seen three days later when the “come on down and help us clean up” cellphone invites rang all the way up to The City Upon a Hill (UCSC) on the third magical day of sharing.

Invisible Forces

Who and what could be responsible for the transformation of 75 River Street? Was it Santa Cruz’s infamous “lone anarchist” or a Mystery Spot leprechaun sighting? Just an otherwise slow weekend for the Boys in Blue? Had there been a promissory rainbow ending at the realtors’ lockbox just before that first night’s heavy winter storm? Just a wrinkle in time?

Or was it, as Santa Cruz County District Attorney Bob Lee has suggested, a felonious and premeditated undertaking of vandalism, trespass and conspiracy by over 300 folks who visited and then left peacefully as planned in a pre-arranged agreement with the police?

In the serendipity of surprise those bank doors were opened, and then that building came to temporary life after three years’ slumber. How the doors were opened initially hasn’t been revealed to most, perhaps to any, of the participants who followed. Almost invisibly, moving along fast, young people, almost like a welcoming committee, handed quarter-page red flyers to marchers, some coming into the building, others milling around in curiosity or support or wondering about the whole scene. The flyers dedicated the prime downtown space for a badly needed community center.

From the former bank’s doorway and massive windows, one could see some Occupy Santa Cruz signs and almost see Occuplaza across the river, and there was PeaceCamp2010 cofounder Robert Facer’s teepee, like a flagship in the tent city in the benchlands of San Lorenzo Park. And after dark, one could see there were yet more uninvolved and unprotected homeless people settling down to sleep along the levee’s edge and street curbs right across from 75 River Street.

The bank-owned building at 75 River Street is not only an empty structure representing waste and indifference while some of the homeless pedestrians are walked to death nearby. For a few years it has also been a cornerstone in the new downtown “forbidden zone” that blocks select homeless people who carry their belongings away from the main downtown Santa Cruz business district via court order, forbidden from parking themselves or their belongings anywhere in the “business corridor” at night.

At Occupy Santa Cruz, there had been some hard traveling and highly charged discussions when “the camp” began to fill up last fall. Both the scope of local homelessness and the Occupy Movement politics were new to many occupiers, so all the usual issues were back on the table week after week once the camp’s ubiquitous tent domes began popping up, and people caught on that they could live and work together.

In less than a month, the camp had grown from 50 tents to over 100, and occupiers grew in their understanding of how poverty and homelessness have been manipulated in our society. Almost 200 tents were inhabited by more than 250 people when the camp was finally torn down by police.

Mistreatment by police

The learning curve unfolded faster when Occupy Santa Cruz folks recognized the same issues were erupting everywhere, from Zuccotti Park in New York City to Seattle to Tampa to Sacramento. Many folks supporting Occupy learned first-hand about the same prejudice and double standards at the hands of police they’d heard about from homeless folks.

As homeless people became more involved in activities with occupiers, other bits of prejudice simply fell away for many. Long before the shameful police department response to the building takeover, and the delayed charges filed two months later against the alleged “property crime” defendants, various groups and individuals within Occupy were intent on finding out what and who was at the bottom of the “hijacked” marchers.

When the protest march was first organized, there had been an expectation of letting the March Against Foreclosures culminate at a foreclosed residence, and then people might have been invited to offer support to whomever was losing their home. But the prospect of a takeover of a bank building was far from what engaged Occupiers had anticipated or been told.

The Anti-Foreclosure Working Group of Occupy Santa Cruz included folks who were well-prepared to continue a dialogue with elected officials and bankers and the California legislature, but that is not what actually unfolded. Some folks backed away altogether, whether following their instincts or a sense of shock at this turn of events. Some people stood around outside the building, meaning to be supportive generally, yet needing their questions answered. The marchers who entered, later joined by other people after the news went out, whether using courage or naiveté, made history.

Police lined up between the sidewalk and the building, leaving people gathered between black-and-acrylic-clad cops, and the bank building’s door. Cops were practicing standing in a straight line, it seemed, with a few officers talking with the surprised marchers, then they left. Not a word of warning about trespass was uttered while the police were there.

For days, after observing Occupy Santa Cruzans react in abrupt and stunning denial to a compliment from San Franciscans about the “building takeover … brilliant idea,” I felt the group could be torn asunder because of “tactics,” invisible lines of authority, and incomplete communication.

After the building takeover, and before indictments came down, it seemed that Occupy Santa Cruz was left with a silent gap between the few supporters of the property crime and the greater number of occupiers who determined to “look away” and focus on other work. Nonetheless, further growth came and Occupy SC seems stronger now, though leaner.

More recently, Occupy Santa Cruz helped launch a campaign to educate and seek out more allies for the Santa Cruz Eleven before the trials began. Occupy SC set up a treasury account immediately after the first indicted defendant was taken to jail (instead of simply being served with a notice to appear in court). And Occupy SC continues to be supportive and to cultivate widening solidarity in response to City and County government’s heavily publicized witch-hunt. Also, supporters of Santa Cruz Eleven who attend the eleven’s weekly meeting all appear to be from Occupy SC.

‘Empty buildings are the crime’

Nobody seems to be talking directly about 75 River Street nowadays, neither in the streets nor around the courthouse hallways. Yet the liberation is far from forgotten.

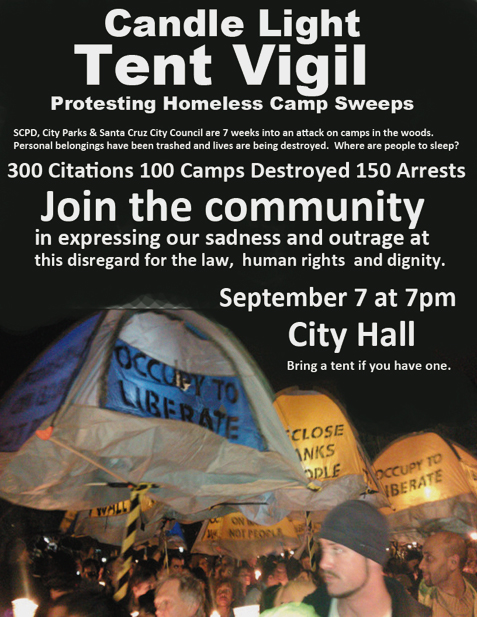

“Empty buildings ARE the Crime!” declares a sign at a recent rally and vigil to support attorney Ed Frey’s and homeless survivor Gary Johnson’s courageous stand for homeless sleepers. Now both men are serving time for “illegal lodging.” The handheld sign alludes to 75 River Street, still for rent or sale, again off limits, now trussed up with barbed wire and kamikaze decor.

The district attorney claims over $30,000 in damages following 75 River Street’s brief “awakening” from Nov. 30 to Dec. 2, 2011. On behalf of “the People of California,” the district attorney indicted eleven alleged perpetrators for this crime, accusing them of opening the bank building and exposing it to harm.

The eleven people accused were selected as scapegoats by a vigilante maneuver when the Santa Cruz Police Department broadcast invitations to locals, citizens, and news-watchers to call in the names of “anyone” whom they recognized in photos flowing from community reporting and police department videos.

Fully two months later, police fingered the following people, who were named by random callers, with Judge Ariana Symons signing the indictments: Brent Adams, Franklin Alcantara, Bradley Stuart Allen, Alex Darocy, Desiree Foster, Becky Johnson, Cameron Laurendau, Robert Norse, Edward Rector, Gabriella Ripley-Phipps and Grant Wilson.

Instead of finding anyone whom their investigators could link to the building’s opening, or even anyone suspicious, they were arresting people based on community recognition — online!

Lots of photos from Occupy Santa Cruz’s Foreclosure March were made public, along with cop videos, videos and photos taken by later visitors to the building, even photos from the two community news photographers who got indicted (see Indybay Santa Cruz’s articles and photos).

So it was not truly a “random” selection of scapegoats. Clearly, the state’s process was slanted to capture media workers, community activists and caregivers who are known to the public and whose apparent presence in the bank building seems more incidental than fundamental, more reportorial than conspiratorial. This process alone makes it appear that the Occupy Movement was their target, more than finding lawbreakers.

Meanwhile, last winter, as if in the spirit of “kick ‘em while they’re down,” Santa Cruz County sheriff deputies sacked Occupy SC’s OccuDome on Water Street while Santa Cruz police flattened the camp in San Lorenzo Park, flanking homeless and Occupy campers from both ends like an army, with not even a full day’s warning, and with City dump trucks following behind their formation.

This over-the-top paramilitary assault on December 8 came a week after the bank building’s absentee landlord, a real estate agent, was located and the lights went out at 75 River Street.

It all could have been handled with patience, a bag of grass seeds to restore the lawn, and a few honest, inclusive planning conversations. Instead, the state seems to be bent on burning through as many resources as possible in an effort to demonize activism and repress people simply for expressing First Amendment rights or civic concerns.

But learning to collectively reseed the courthouse lawn and the park was not even considered.

The police jump the gun

While Santa Cruz Mayor Don Lane and others were still attempting to work with Occupy SC — and even supported the camp’s existence — Police Chief Kevin Vogel jumped the gun, crashed the party, and further diminished the very lives of homeless people among the campers.

The police apparently over-ruled even the dialogue with Santa Cruz County’s environmental safety agents. Steve Pleich, an Occupy SC legal liaison, City Council candidate and homeless ally, reminds us: “The police action pre-empted campers’ Temporary Restraining Order already filed in San Jose’s Federal Court for a hearing (one week later),” a legal request both the Board of Supervisors and City Council members had acknowledged prior to the police devastation.

Brent Adams, one of the Santa Cruz Eleven defendants, said, “75 River Street is important to talk about. It touches on so much. But the prosecution (of the Santa Cruz Eleven) has eclipsed the many issues the building take-over may have intended to shed light on, and many others inadvertently. 75 River Street will remain an important symbol of the massive glut of banking and real estate culture, and of peoples’ resistance.”

Adams was supportive of campers and the tent city last winter. He is currently helping document a spree of anti-homeless assaults, criminalization and “go back where you came from” bus ticket offers given out en masse to homeless people.

Now, an interdepartmental gang of City staff led by SCPD police officers has resorted to using intimidation against homeless people and has roused greater anti-homeless hatred throughout the town. They intensified their banishing act in preparation for the tourist influx during Labor Day weekend.

We are paying police and public officials to illegally destroy the lives of homeless people, who are being shoved — at best — back into the bushes and literally into the river, without their clothing or necessary personal belongings.

When he is not being redundantly called to court, Adams has been able to talk with some of the people whose tents were destroyed, and others who have been cited for “still being,” as a young local puts it.

Last winter, after witnessing more than a hundred heavily armed police officers destroy the Occupy tent city, it came down to feeling like we are peons in a struggle between Homeland Security goals and the U.S. Constitution.

For many younger activists and proponents of social, cultural and public change, both observers and displaced, it came as a shock to see police officers literally stomping people inside their minimal homes. And now, those sadistic squads are fanning through town with the same impunity displayed last December.

Santa Cruz 11 trial preparations

Early on, the court held hearings and determined that community-based reporters from such media outlets as Santa Cruz Indymedia and Free Radio Santa Cruz are indeed engaged in journalism, and not inherently criminal behavior.

And now the Santa Cruz Eleven — meaning the five to seven remaining defendants whose charges have not been tossed out yet — face a California Superior Court Judge who has already shared his frustration from being faced with consistently faulty evidence. Two of the eleven had their cases dismissed earlier because of corrupted evidence. Then the district attorney refiled charges against them, and in September, Judge Paul Burdick will see if the new charges have any better chance of sticking.

Hearing after hearing — ten or more — demand that all or any combo of defendants and their attorneys be present. It has been six months since defendant Johnson was jailed, though she never even entered the building in question. Many defendants haven’t even been able to see the evidence the district attorney intends to present in an attempt to show they were conspirators bent on destruction of property.

“In these Santa Cruz Eleven cases, the prosecution is the punishment,” quipped codefendant Becky Johnson, one of the eleven whose life and earning ability has been diminished by the indictment and long, drawn-out, legal process.

On top of everything else, these scapegoat defendants are dealing with a judge who scolded their lawyers during court, ordering them to not make him angrier. The judge also suppressed defense counsel’s testimony which included lists of unshared evidence, even though all grievances and concerns he had referenced on both August 17 and August 20 pertained to the prosecution.

This past month, yet another compulsory court date for seven remaining defendants, plus each of their attorneys, was held on August 20, 2012. Judge Burdick emphatically expressed his impatience toward Assistant District Attorney Rebekah Young’s evidence-sharing inconsistencies and stonewalling. Nonetheless, it seemed during an emotional outburst that the judge intends to get at least one “guilty” occupier from among the People’s scapegoats before the trial ends.

Impropriety by district attorney

Robert Norse, Free Radio Santa Cruz programmer and one of the Santa Cruz Eleven, said of the August 20 pre-preliminary hearing, “Impropriety after impropriety was revealed by the six defense attorneys, showing not only that D.A. Rebekah Young had improperly denied (the Santa Cruz Eleven) their right to view the evidence against them, but also that she had violated Burdick’s court orders to provide that evidence. And then she lied about it.

“Burdick, however, not only refused to throw out the charges, he refused to renew his threat of the strongest sanction — dismissal of charges — and he delayed any discussion of sanctions until January. He also refused to allow the defendants (or their attorneys) to go on record with the evidence of Young’s falsehoods.”

Judge Burdick was demanding a higher caliber of legal work. In response, District Attorney back-up Jeff Roselle tried to deflect this concern by claiming “the sanctity of private property has been violated.”

As people left Burdick’s courtroom, Santa Cruz Eleven defendant Gabriella Ripley-Phipps questioned, “What about the sanctity of our rights to free speech, to a fair and speedy trial, to dissent?” This trial pits vacant, unused real estate against human life with little regard for the presumption of innocence.

Burdick himself had earlier ruled against some of the state’s shaky evidence as irrelevant and dismissed one case because a police officer contradicted his own testimony.

Judge Burdick and all of us watching can see D.A. Young’s bind. Yet Burdick has not quite come to realize there is a bigger reason the evidence isn’t working against these defendants — namely, that they simply didn’t commit the crimes for which they have been indicted.

The legal phase of this struggle began when Johnson, the first defendant, was carted off to jail in early February, as though she were a dangerous criminal who would fly, rather than the householder and caregiver for three disabled adults whose well-being depends on her reliability.

Watching seven attorneys from three cities trying to match up their calendars with the judge’s is like going to a bad Bingo game. Unfolding into next year, the preliminary hearing again was reset to Jan. 4, 2013, and a trial could finally begin on January 7.

Credit for a beautiful vision turning into a more participatory way of living goes mostly to whoever opened that door to vacant 75 River Street. Also, kudos to whoever had the foresight and audacity to lead, and perhaps, to some degree, to capture, an organized working group’s Occupy Santa Cruz March Against Foreclosure, right up to the former bank’s door.

I believe those autonomous wizards are not among the eleven people who were accused of felony vandalism, conspiracy and trespass. And I’m certain the Santa Cruz Eleven are not the people who caused, or triggered, the landlord’s $30,000 bill for the alleged clean-up costs from three amazing days spent inside.

For many who went to 75 River Street, it was their only shelter in town during last winter’s storm. For a gaggle of folks, it was a chance to catch up with one’s dirt-poor allies and friends over-busy with survival, or to get fed, or to talk all night about how people might sustain a community center that doesn’t discriminate or exclude. Some folks simply slept, hopefully deeper than they are able to sleep alone outdoors, since in Santa Cruz, having no home means being forced to walk around all night, or hiding and becoming a criminal — simply for trying to rest in a city which tries to outlaw sleeping.