by Joan Clair

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]artin de Porres was born in Lima, Peru in 1579. His mother was a freed African slave and his father was a Spanish aristocrat. After seeing that his newborn son’s skin color was black, Martin’s father refused to acknowledge his paternity. Martin was brought up in poverty, along with his sister Joan who was also not acknowledged in spite of her lighter skin color.

In that era, many groups suffered discrimination and mistreatment, including Indians, Africans, poor women who had no dowries, orphaned and homeless children, and animals. Those discriminated against were regarded as not rational in comparison with the Spanish aristocrats who considered themselves possessed of reason and therefore superior.

Martin broke through all these stereotypes and began offering charity wherever it was needed. At a very early age, when his mother gave him what little money was available to buy food for the family, Martin often would come home empty-handed, for he could not pass by an injured, homeless or hungry human or animal without trying to help. As a child, he was punished severely for his generosity. Nevertheless, his compassion towards those in need remained one of the hallmarks of his entire life.

After Martin’s father finally acknowledged his paternity, he began an apprenticeship with a barber-surgeon. A barber in those days was a doctor and herbalist; he did not simply cut hair, so he learned about medicine and caring for the sick, and his concern and compassion for those suffering ill health would become a lifelong commitment.

At the age of 15, Martin felt drawn to the Dominican Order in Lima and was accepted as a tertiary, the lowest ranked member of the order — one who was expected to do all the menial tasks. He performed these tasks for his entire life, refusing to enter the priesthood of the order even though his father’s influence would have enabled him to do so. He was not interested in rank, although eventually he became a lay brother in the Dominican Order.

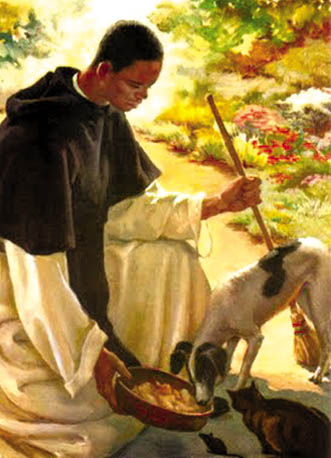

The holy card of Martin de Porres portrays him with a broom, an acknowledgement of his humility and his dedication to humble work. Yet Martin served in many other ways. With his training as a barber-surgeon, he served those who were discriminated against at no charge. He cared for the ill, especially those who were poor and homeless, and often brought them home to the monastery.

He also treated homeless and injured animals. When he was told by his order that he could not bring ill and injured humans or animals into the monastery any more, he turned to his sister Joan. Joan took in the humans and the animals, creating the first free clinic for people, and the first free veterinary clinic for animals.

Martin gave away thousands of dollars worth of food and clothing to poor and hungry people each week, after begging these donations from wealthy families. He also raised money for an orphanage for Lima’s homeless and abandoned street children. And he raised money for dowries for women who otherwise would have ended up on the street as beggars or been forced into servitude.

Martin stood up for poor people and animals, even from his lowly rank in the Dominican Order. He was the advocate of those who needed him. On one occasion, after he was instructed not to bring to the monastery any more sick and homeless people, he found an old man on the street near death and covered with sores. He brought the man to his monastery cell and nursed him back to health.

In her book, Martin de Porres, Hero, Claire Bishop describes the reaction of one of the lay brothers who was dismayed by Martin’s act of kindness and said, “It’s an outrage … Look at those blankets! The [monastery’s] blankets! All stained with blood and pus. I shall complain.”

Martin’s response was, “Listen to me. Blankets, I can wash. Soap and water will remove stains. But it would take more than soap and water to clean a soul who failed to help a neighbor in need.”

Even after he explained that compassion is more important than clean blankets, Martin was reported to the prior of the monastery for this supposed offense.

The prior told Martin, “As a lay brother you have to obey orders from your superiors. Is that clear?’”

Martin replied, “Was it really wrong to put charity before obedience?” In faithfulness to the precept of charity, Martin had committed an act of “civil disobedience.”

One can infer that if the old, ailing man that Martin helped had been well-dressed and of aristocratic lineage, he might have been more welcome in the monastery. This mistreatment of destitute people as social pariahs echoes down through the ages to the present day.

In her article, “Block by Block: A BID by Merchants to Seize the Public Commons,” [Street Spirit, January 2013], Carol Denney described an incident in which an “ambassador” of Block by Block — an organization whose slogan includes “cleaning and hospitality for downtown improvement districts” — repeatedly swept all around and under an impoverished woman sitting on a public bench wrapped in a blanket with her few possessions.

Denney wrote, “It’s safe to suggest that no well-dressed bench-sitter would be similarly treated.” She also pointed out that the ambassadors “steamwash sidewalks so repeatedly that anyone carrying everything they own is likely to have their few belongings soaked and ruined.”

Berkeley’s ambassadors have turned Martin’s lesson in compassion on its head by using an obsession with “cleanliness” to destroy the spirit of charity. His entire life teaches us that the most essential “cleanliness” is an inner state of charity that results in serving one’s neighbor.

Charity was so deeply embedded in his soul that he became known as “Martin of Charity.” His understanding of charity extended to all living beings, not humans alone. Charity, in the fullest sense of the word in the Hebrew scriptures, means compassion with justice. Martin embodied this. He believed that charity was placed deep in the soul by God.

Charity is not only help to the poor by those who are wealthier. Charity has deeper spiritual roots. It means love and good will towards our fellow creatures. Theologically speaking, charity means the benevolence of God towards all creatures. In other words, charity is “love thy neighbor as thyself.”

Rather than being defiled by the discrimination he experienced as a result of the color of his skin and the poverty of his early upbringing, Martin learned deep sensitivity and kindness towards all those facing similar hardships. And he served not only sick and impoverished humans and animals, but also the wealthy aristocrats when they, in desperation, turned to him.

Defiled, uncharitable thoughts lead to uncharitable actions such as trampling on the rights of the poor, increasing their invisibility through Sit/Lie laws, and cutting back on the few protections the poor have, such as food stamps and housing vouchers. It is predicted that more than 140,000 low-income families will lose their housing vouchers as a result of budget cuts triggered by sequestration.

Yet, it is not the poor and homeless who are defiled inwardly or made “unclean.” Those who support these anti-homeless measures reflect their own inner defilement. In their refusal to embrace charity, they become complicit in society’s neglect and rejection of those in need. Opportunities for charitable actions are to be embraced as opportunities for cleansing and healing. Martin knew this, and so did Jesus.

Denney’s article on the Berkeley ambassadors touches on this. She writes, “The point remains that demonizing poor and homeless people helps smooth the way for discriminatory laws, discriminatory practices, and a population unable to hear or respond to honest human need.”

In Denney’s analysis, “There is a very tangible human cost to allowing greed to play the largest role in our community and our legislative priorities.”

One thinks of the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 when government-controlled systems such as health care, rent control, and old-age pensions were discarded. Countless families fell apart, and children as young as four years of age were forced to live in the street. As a result, in the mid-1990s, estimates of homeless children living on the streets in the former Soviet Union ranged from hundreds of thousands to two million. An estimated 1.3 million homeless children live on the streets in the United States today.

As our charitable laws are threatened more and more, what will become of the non-affluent people in our nation? For that matter, what will happen to animals in factory farms when bills are proposed in California and passed elsewhere in the nation making it more difficult for whistleblowers to report abuse?

Turning now to his charity towards animals, the holy card of Martin depicts a cat, a dog and a mouse all drinking soup from the same bowl without injuring each other. Animals were not adversaries in Martin’s presence, and he himself was a vegetarian out of respect for animals.

In A Wounded Innocence: Sketches for a Theology of Art, Alejandro R. Garcia-Rivera suggests that the bowl of soup in this iconic image is actually a Eucharistic meal to which all of creation is called.

The ultimate, charitable community is reflected in the words of Isaiah: “The wolf shall live with the lamb, the leopard shall lie down with the kid, the calf and the lion and the fatling together, and a little child shall lead them” [Isaiah 11:6]. Garcia-Rivera believes that Martin de Porres is that little child that can lead humanity.

There are many examples of his charity towards animals. As described by Bishop in Martin de Porres, Hero, he saw a mouse in a trap in the monastery, and set it free. The sexton chastised him, saying the mice have been eating the altar cloths, which the monastery cannot afford.

“But,” cried Martin, “mice mean no harm. They are just hungry.” Taking the sexton’s concern to heart, Martin, like a pied piper, called on the mice in the monastery to follow him out to a barn. He told them that if they would live there, he would feed them every day, which he did, from kitchen scraps. From then on, the monastery was free of mice as a result of Martin’s act of charity.

The most extraordinary account of his charity towards animals, however, is the story in which Martin rescues a dog from an unkind, disloyal owner. Apparently, an 18-year-old dog had mange and many complained about his smell. Giving in to the complaints of others, his owner, the steward of the monastery, had the dog killed. Martin rescued the dog, and brought him back to life and health, saying to the dog, “Now, don’t you ever go back to your ungrateful master. You must know by this time how little your long years of faithfulness have been appreciated.”

When Martin was dying, a doctor wanted to apply a poultice made of the blood of freshly killed young roosters to relieve him of his headaches. Martin refused, saying it was “a pity to kill the poor animals to concoct a useless remedy.” This story was recounted in Giuliana Cavallini’s inspiring biography, St. Martin de Porres.

The prayer card of Martin is a true portrayal of what people valued in him the most. It is the holy card most popular in the Americas, second only to the holy card of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

Martin is shown holding a broom. He kept up his so-called menial tasks until the end of his life. His broom was never used to afflict the poor and the homeless, to sweep the streets of the most oppressed, to render the poor even more invisible.

In the background of one version of the card is an ill and bedridden man. Martin’s works of charity included healing and ministering to the poor and homeless.

Three animals, often adversaries, drink from the same bowl of soup in Martin’s presence — a dog, a cat and a mouse. A dove, symbolic of the holy spirit, according to Garcia-Rivera, transforms the soup into a Eucharistic meal for all creatures — a communion, a community of love.

In our era, marked by widespread poverty and collective amnesia about the supreme importance of compassion and justice, Martin de Porres provides an example for all of us of the ways in which charity within becomes manifested as charity without — charity on all levels, for all creatures.