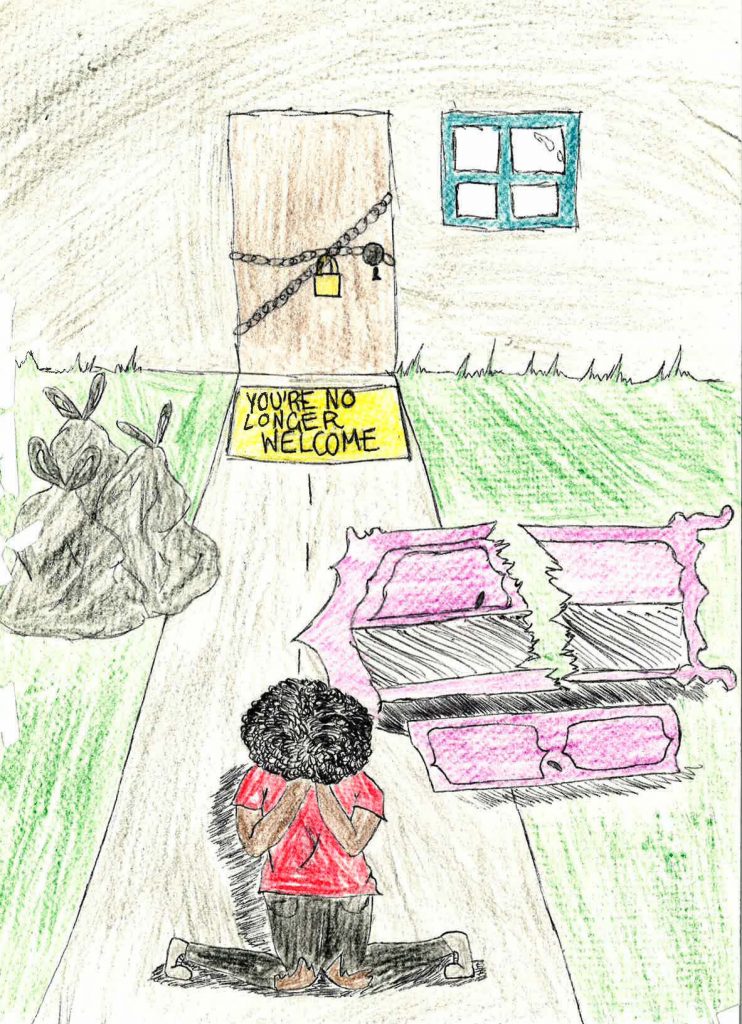

In the eyes of sixteen-year-old Hunter McLaughlin*, “coming out” would be a gateway to a new life. It would give him the opportunity to live more honestly and with a renewed sense of authenticity to his true self. But when he told his parents that he was transgender, the “new life” that awaited him was one plagued by emotional abuse, threats of violence, and seemingly endless conflict. Hunter’s “new life” was a life on the streets.

After packing a duffel bag of his most important possessions, Hunter was on his own. At first, he sought entry into one of Oakland’s few homeless shelters, but it was not long before he began to reconsider his options. After days of sleeping on little more than a fold-out army cot, Hunter had encountered drug dealers, thieves, body lice, and bed bugs. He knew he had to leave, but he didn’t know where to go. Fearing foster care and the possibility of his family finding out his whereabouts, Hunter had little choice.

Within weeks, he had moved from friends’ couches to alleyways and public parks. While he had found and befriended several other individuals living on the streets, concerns over his worsening mental health, substance abuse, and the possibility of sexual assault imperiled the “new life” he had been promised. Forced to drop out of high school for truancy, Hunter felt helpless and misunderstood. Life as a young, African American transgender person, in Hunter’s words, meant living “a life [he] could not possibly have been prepared to live.” In many ways, he said, “it was not a life worth living.”

But Hunter has learned far more on the street than merely the art of survival. He learned that his story— while heartbreaking—is not unique. In fact, it is an all-too-commonly overlooked constellation of factors that had put him at an increased risk for both becoming and remaining homeless

More and more, young people in California are at risk of becoming homeless. Within the last year, Southern California cities have seen an astonishing 40 percent increase in the rate of youth homelessness, attributable largely to unsafe and hostile conditions on the street and in adult shelters.

What’s more, these conditions often transform what otherwise might be temporary displacement into chronic forms of homelessness; youth in particular face a higher likelihood of sexual exploitation and a greater susceptibility to follow in the footsteps of destructive habits from their chronically homeless elders.

On top of this, as an African American youth, Hunter was born 83 percent more likely to become homeless than his white peers. Making up a disproportionate amount of the homeless population, African Americans earn less than their white peers on average, have fewer housing opportunities at a higher cost, and are less likely to receive favorable outcomes in health care and the criminal justice system. Historical discrimination has culminated in the dissolution of social safety nets for African Americans, ensuring that what would otherwise have been a momentary placelessness is instead a time of prolonged social and physical exclusion.

Hunter has learned far more on the street than merely the art of survival. He learned that his story—while heartbreaking—is not unique.

But above all, Hunter’s gender identity increased his chances of becoming and staying homelessness. According to a national study conducted by the University of Chicago, LGBT youth between the ages of 13 and 25 are 120 percent more likely to become homeless than their straight peers. Like Hunter, many are forced out of their homes due to rejection by their family, which often results in lasting psychological and emotional trauma.

As a result, an inordinate proportion of those who identify as queer face an increased risk of homeless individuals identify as queer, and are thus more likely to becoming homeless at a younger more vulnerable age, and for a longer period of time. Filled with understandable fear and disorientation, young queer people like Hunter are subject to a near-permanent state of crisis.

Hunter’s story provides immense insight into all of these statistics. His story provides context to ballooning rates of depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and substance abuse. This, in conjunction with other structural barriers, reduces one’s ability to alleviate poverty and hardship, multiplying the likelihood that one becomes and stays homeless. Hunter’s struggle with housing illuminates the larger truths about the nature of familial and societal rejection, as well as about the factors complicating one’s ability to simply “pick themselves up off the streets.”

Hunter’s story, though, is not simply a denunciation of the lack of a safe and affordable place to live. housing. It is at once a critique of our society, a tragedy of humanity, and a common autobiography. It is a description of injustice, and it should be a call for change.

It is human; it is the story of the search for home.

*A pseudonym used to protect the individual’s identity.

Anthony Hackett is a housing rights advocate and Student at Stanford University.