by Lydia Gans

[dropcap]P[/dropcap]rolonged unemployment and rising home foreclosures are driving more and more newly homeless people into homeless shelters, not just for a few nights, but for many months as they try to reorganize their lives. Every night now, most shelters in the East Bay are full.

There is also a population of chronically homeless people, people who have been living outside, sometimes for years. A few live outside by choice, but most subsist on very limited incomes from Social Security disability, pensions, or various programs that do not provide enough to pay rent.

These longtime homeless people find safe, sheltered spots to sleep and keep their possessions. They occasionally spend a night in a motel, but have no permanent housing. It is only when the weather is really cold or rainy that they will seek indoor shelter for the night.

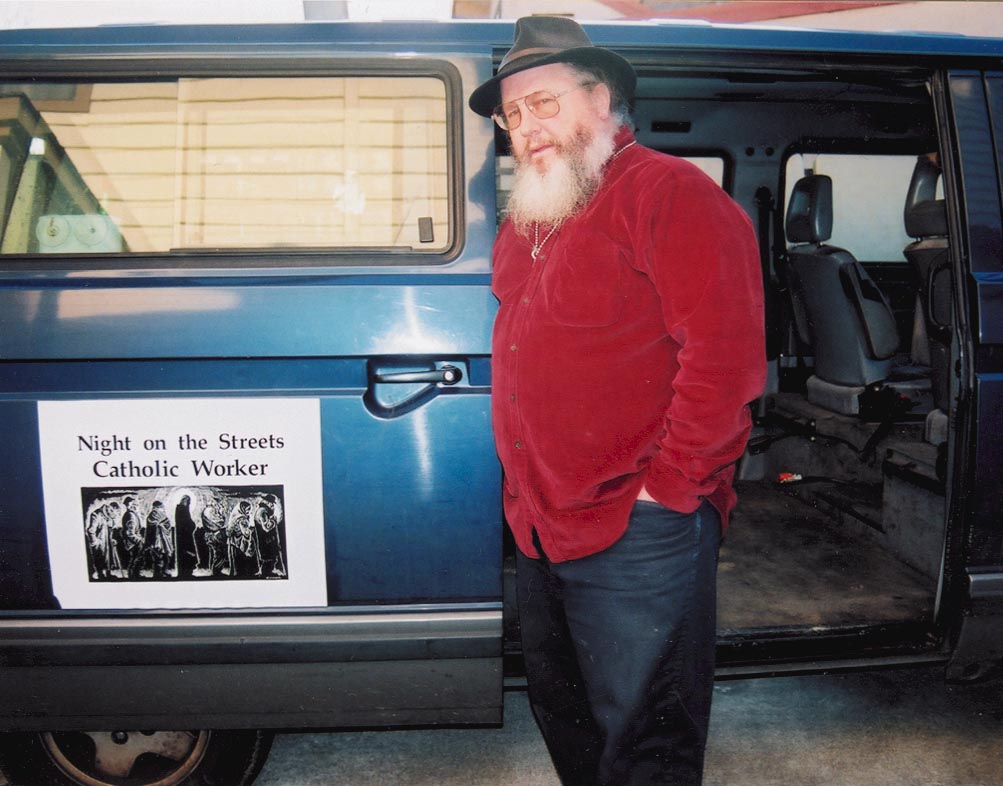

On those occasions J.C. Orton, founder of Night on the Streets Catholic Worker, opens an emergency shelter at the First Congregational Church in Berkeley. It is operated by Dorothy Day House and financed primarily by the City of Berkeley. There is only enough money to open its doors about 35 nights out of the year.

On a recent Monday night in late February, rain and cold had been forecast, so word went out that the shelter would be set up. From 7 p.m. until 10 p.m. that evening, the Berkeley Community Chorus was holding its regular rehearsal in the assembly hall of the church. At 10 p.m., chorus director Ming Luke ended the rehearsal and everyone hustled to stack the chairs and move risers and the piano into the far end of the room.

The exhausted but inspired singers closed their music books and headed for their homes, while outside, J.C. Orton gave out tickets for the shelter to the homeless people waiting at the church doors. The space can only accommodate 50 people. On this night, 10 people had to be turned away. There is no place for those 10 persons who were turned away from this shelter of last resort.

By about 10:30, everyone was settled inside. The people sleep on foam-covered mats on the floor. “Don’t have to worry about bed bugs,” Orton explained. Everyone is provided with clean sheets. It is warm enough so that the sheet is sufficient.

On the first four or five nights that the shelter operates, Orton also gives out sleeping bags to anyone who might need one. “Then, if we’re not open the next night, they get to take the sleeping bag with them which allows the effects of the shelter to extend beyond the shelter itself,” Orton said. “They come to the shelter without a sleeping bag, they leave with a bag. It’s like an added bonus.”

For the next eight hours, these 50 homeless people can rest comfortably with a roof over their heads, but by 6:15 a.m., everyone had to be out so the place could be cleaned by 7 a.m.

The First Congregational Church has been providing the shelter space for the past two years free of charge. St. Mark’s Episcopal Church was home to the storm shelter for the last seven years prior to that, also without charge.

Dorothy Day House employs Orton to run the shelter. He is usually there when it opens, often with snacks or, on some nights, with soup left over from the Catholic Worker meal at People’s Park. Ten people act as shelter operators, actually spending the nights on the premises. They are people who themselves are homeless or have experienced homelessness.

Orton keeps data on the characteristics of the shelter population. He observes that there are usually about four times as many men as women. There are eight or ten veterans who show up regularly. As for age distribution, 5 percent are 18 to 25, 65 percent are 25 to 55, and about 30 percent are over 55. Over the years, the aging of the baby boomer generation is showing up in an increasing proportion of older homeless people seeking shelter.

Orton expresses deep commitment to keeping the shelter going in bad weather.

He said, “I think it’s a fantastic situation where we’re able to take 50 people a night for somewhere up to 40 nights, or 2000 people-nights, and shelter these people. It’s not just a matter of giving them a cookie or a blanket or a hearty handshake or wishing them the best, but taking the responsibility for 8 to 12 hours on all those nights — taking a personal responsibility for them. And the satisfaction of being able to give that depth of service, to my mind, is overwhelming.”